Meet Georg Cantor - a Mathematician (and an impressive violinist). The first mathematician to really understand the meaning of infinity and to give it mathematical precision. Cantor revolutionized Mathematics with his groundbreaking work on set theory - the following is a small excerpt of his brilliance.

So let us follow his footsteps and explore the realm of the infinite!

The basics - Counting

Example: Consider that you are in a classroom with 200 seats. The classroom is completely full. How many students does the classroom have?

200 right?

How did you know that without counting the students there?

Your reasoning probably goes like this:

- There are 200 seats

- Each chair has exactly one student sitting on it

- So the number of students and the number of the chair must be the same - 200

- So, there are 200 students

What this example strives to show is that comparison is at the basis of counting. Let us formalize this idea of comparing. We only need the following rule for that:

Rule: If you have 2 sets (collection of objects) - say, A and B have the same size1 if:

- We can pair each object of A with an object of B

- No element (from A or B) is left out

- Every element from A pairs with a unique element in B (and vice versa)

Remember this rule

Using this rule counting becomes elementary - For any given set, find a corresponding standard set with the same size, and we are done. These standard sets have pre-defined sizes:

| Standard set | { 1 } | { 1, 2 } | { 1, 2, 3 } | … | { 1, 2, 3, …, 42 } | … |

| Size | 1 | 2 | 3 | … | 42 | … |

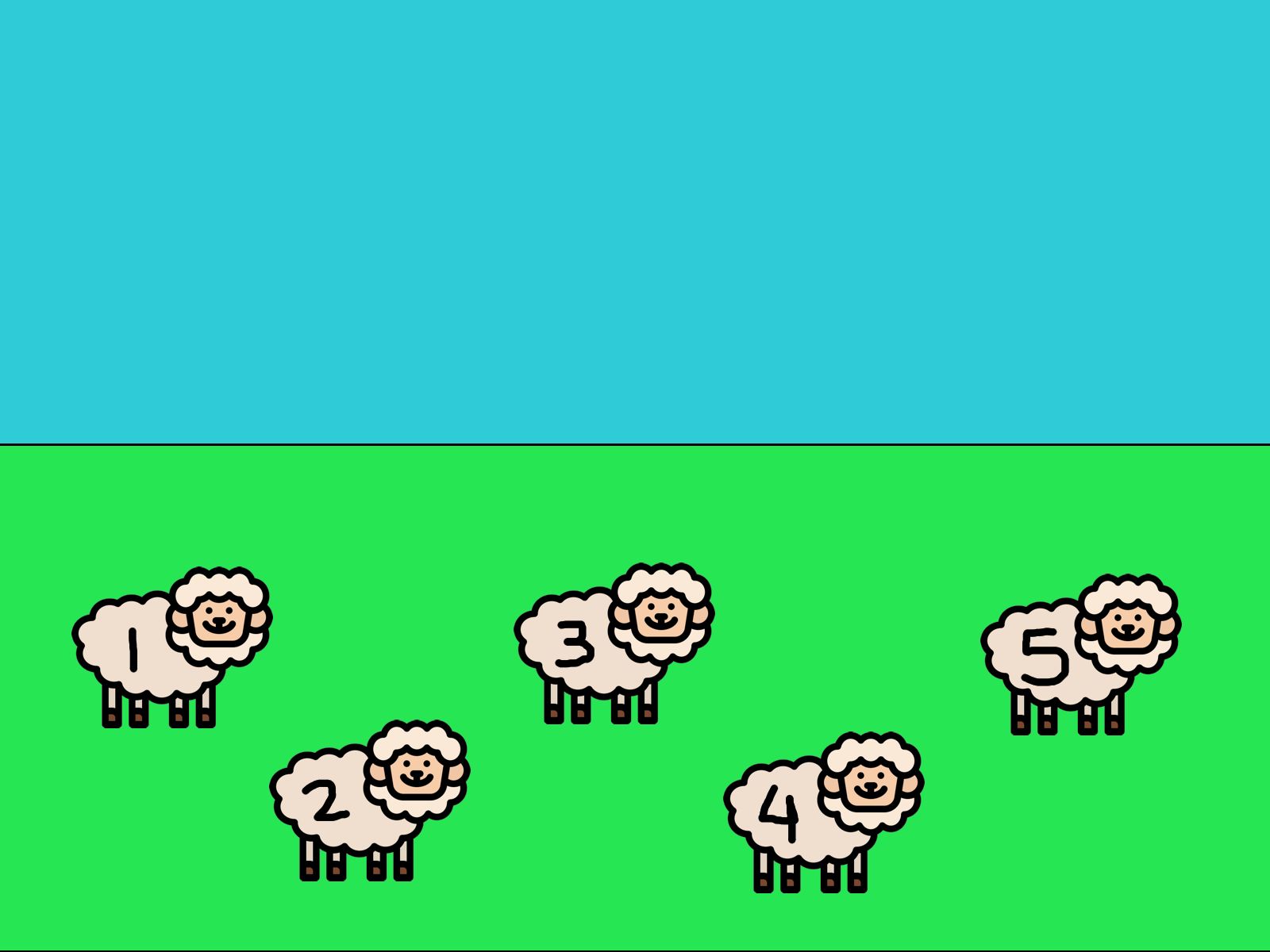

Example

- How would you count the number of sheep in the above image?

- The picture shows one possible pairing between the sheep in the image and the standard set {1,2,3,4,5}.

- No sheep is left out and each sheep is paired with a unique number

- So the number of sheep is the same as the size of the standard set {1,2,3,4,5}

- So, there are 5 sheep

What do you mean that’s why I can’t sleep at night?

Although this may seem like an overly complicated way to count things, this approach generalizes well to the infinite case, and we will be able to count endless sheep in no time.

How would do we count the infinite?

Before counting the uncountable, let’s start with a more straightforward question - how do we define it?

Try it out. How would you define an infinite set?

A few possibilities are:

- An infinite set is a set whose elements can not be counted.

- An infinite set is one that has no last element.

- An infinite set is a set that is not finite.

We will settle on a much subtler definition:

A set is infinite if at least one of its parts has the same size as itself.2

In other words, a set is infinite if we can find a valid pairing between the set and one of its parts

Why use this strange definition?

This definition is useful for 2 reasons:

i. It uses only previously defined terms i.e., the size of a set and the rule we defined earlier

ii. It is easy to check if a set is finite/infinite using it. We just need to construct a suitable pairing

The earlier definitions fail in at least one of the above.

This definition should make sense intuitively.

If a set was finite, then each part will have a size smaller than it.

Example The set of primary colors - { Red, Green, Blue } has a size of 3.

We can verify that it is finite by checking that each part of Z has a size smaller than 3.

| Parts | Size |

|---|---|

| { Red }, { Green }, { Blue } | 1 |

| { Red, Blue } { Green, Blue } { Blue, Red } | 2 |

Now consider an infinite set - say the counting numbers \(( 0,1,2,3,... )\)

The even numbers \(( 0,2,4,6,... )\) are (clearly) a part of them. Do they have the same size?

Yes! the pairing given below maps every counting number to a unique even number. Further no number is left out.

| Counting number | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | … | n | … |

| Even number | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | … | 2n | … |

The pairing satisfies all the rules we defined earlier!

That must mean that they have the same size!

So per our definition, the counting numbers are infinite. What should we call their size? Let us denote it by the Hebrew letter \(\aleph_0\). We have our first result:

The size of the counting numbers is \(\aleph_0\).

Are there more?

The next logical question is:

Have we discovered all the possibilities, i.e. do all infinite sets have the same size (\(\aleph_0\))?

Let’s try out a few examples.

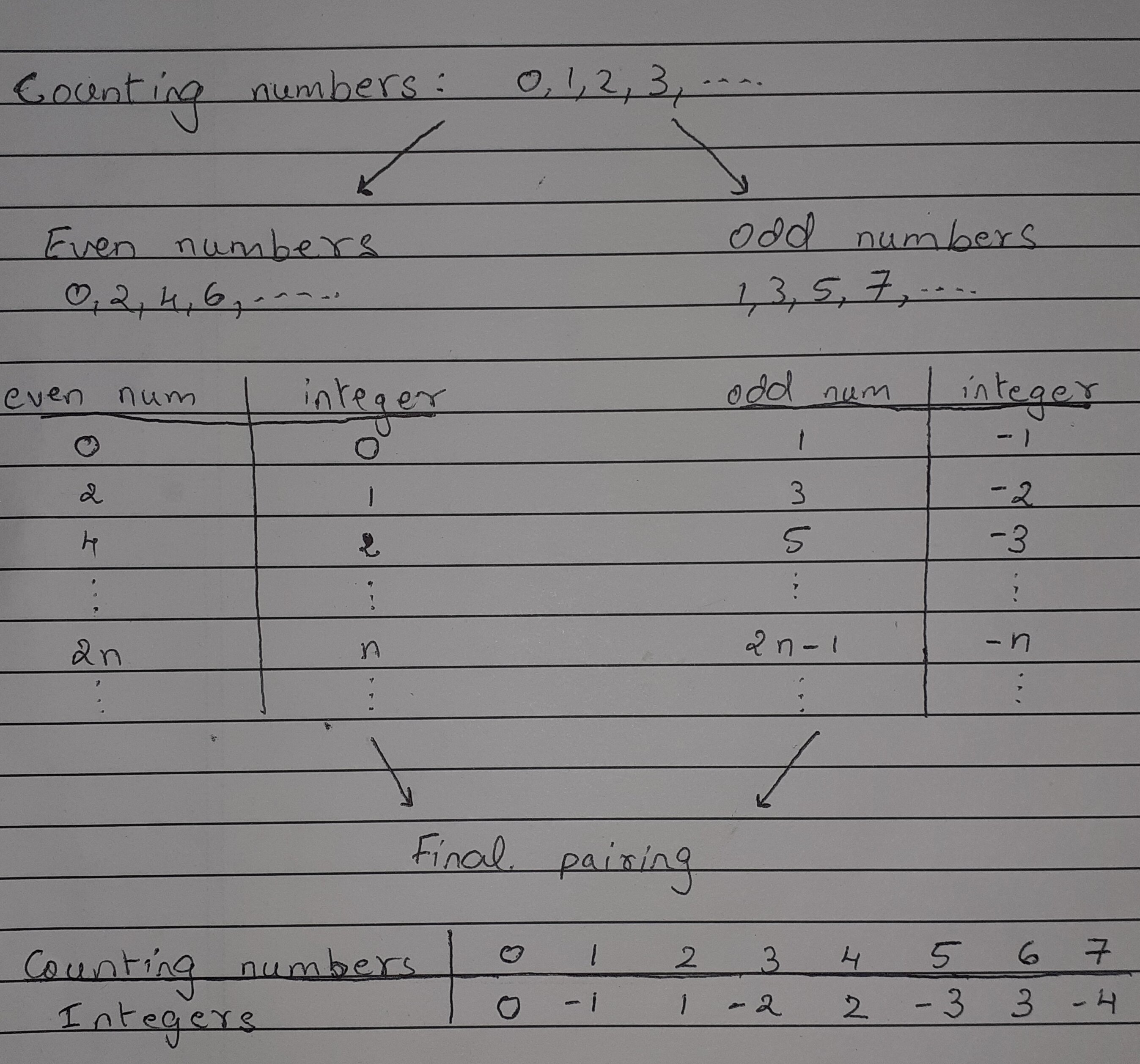

The integers

1

Z = {..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...}

Surely, the integers must be bigger than the counting numbers? After all the counting numbers are a part of the integers.

It turns out that they have the same size.

How do we show this? we construct a pairing between the two.

Odd numbers pair with negative numbers

Even numbers pair with positive numbers

Since our pairing satisfies our rule, they must have the same size as the counting numbers.

i.e. The size of the integers is also \(\aleph_0\)

The rational numbers (fractions)

1

2

3

Q = {all numbers that can be written as p/q, where p and q are integers}

= {all numbers with a finite decimal representation}

= {..., 1/2, 4/3, 2=(2/1), ...}

\(\mathbb{Q}=\Big\{\dfrac{p}{q} \ | \ p,q \in\mathbb{Z} \Big\} \quad \textrm{(The formally correct definition of the rational numbers)}\)

Surely all the fractions must be bigger than the counting numbers?

Not only do they contain the counting numbers, but there is an infinite number of fractions between just the first two counting numbers!

1/2, 2/3, 3/4, … n/n+1, … are all between 0 and 1

Strangely, this is also not true.

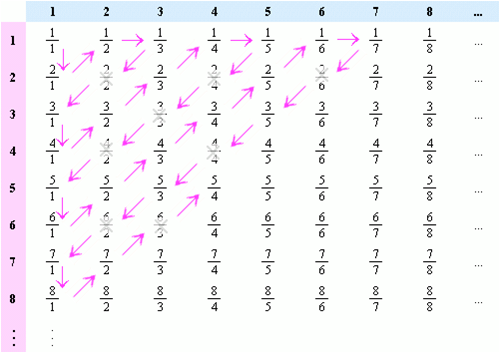

Constructing a pairing between the counting numbers and the rational numbers is a bit tricky.

One possible pairing is shown below:

Just follow the arrows:

- 1/1 is the 1st, so it pairs with 1

- 2/1 is second so it pairs with 2

- …

- 2/3 is eighth, so it pairs with 8

- …

- Cross out fractions that we already counted. So any fraction that is not in it’s simplest form is crossed out.

- 0/1 pairs with 0

Final pairing

| Counting number | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | … |

| Fraction | \(\frac{0}{1}\) | \(\frac{1}{1}\) | \(\frac{2}{1}\) | \(\frac{1}{2}\) | \(\frac{1}{3}\) | \(\frac{3}{1}\) | \(\frac{4}{1}\) | \(\frac{3}{2}\) | \(\frac{2}{3}\) | \(\frac{1}{4}\) | … |

So the rational numbers also have the same size - \(\aleph_0\)

These results may appear counter-intuitive at the beginning, and you wouldn’t be the only one. When Cantor first published his theory, it encountered resistance from mathematical giants of his time as well).

But once you understand the mechanics of defining pairings, intuition follows. If you want more such examples - check out Hilbert’s hotel - a brilliant thought experiment designed to help you wrap your mind around this counter-intuitive theory.

This result, in particular, baffled me. There are infinite fractions between any 2 counting numbers (in fact, there are infinite fractions between any two fractions). And yet, they have the same size!

Gong beyond - Cantor’s brilliant proof

While exploring this particular definition of size, Cantor stumbled upon a strange result.

He found a set bigger than the counting numbers. How could that be? The counting numbers are already infinite?

The real numbers

1

2

R = { All numbers that have a (finite or infinite) decimal representaion }

= { All numbers that are either rational or irrational }

\(\mathbb{R} \supseteq \{-3, \frac{-1}{2},\ 0,\ 0.5,\ 1.414,\ \sqrt 2,\ \pi,\ \frac{42}{9},\ ... \}\)3

We shall show that the reals are bigger than the counting numbers using Reductio ad Absurdum (also known as a proof by contradiction).

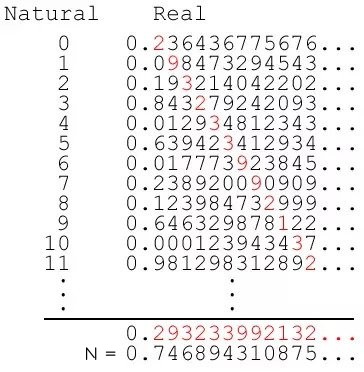

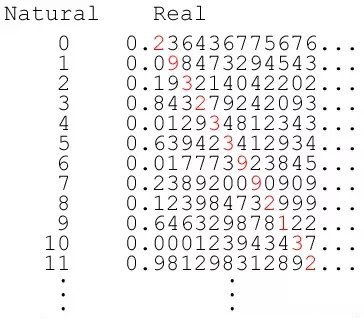

Suppose the size of the reals was the same as that of the counting numbers

There must exist a pairing between them (By definition)

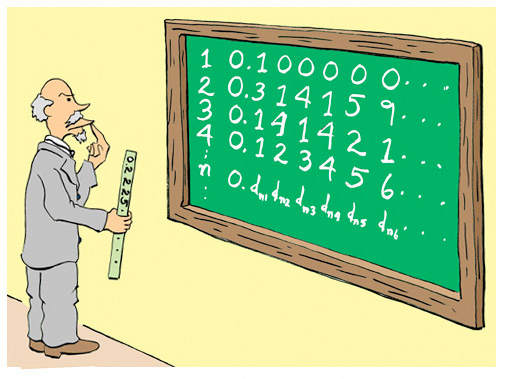

(Say, it looks like the figure below)Note: That this is just one possible pairing, our argument is independent of the actual pairing. It only relies on the fact that a pairing exists.

- Construct a new real number N as follows:

Go to the 1st number on the list, and look at its 1st decimal place (2 in the diagram)

Let N’s 1st decimal place be any number other than 2 (say, 7) (so far N = 0.7)

Go to the 2nd number on the list, and look at its 2nd decimal place (9)

Let N’s 2nd decimal place be any number other than 9 (N = 0.74)

Carry this process forever, so in general

Look at the ‘m’th number on our list; specifically, it’s ‘m’th decimal place.

Choose any digit EXCEPT this one for the mth decimal place of N

Using this we get N = 0.746894310875… - Let us show that N does not belong to the list

Now since N is a real number, N must be somewhere on the list.

It can’t be at the 1st place because it differs from the 1st number at the 1st decimal place.

It can’t be at the 2nd place because it differs from the 2nd number at the 2nd decimal place.

…

It can’t be at the Nth place because it differs from the Nth number at the Nth decimal place.

… - This argument shows that N does not fit anywhere on our list4. But N is clearly a real number.

- So our initial assumption (that every real number can be paired with a unique counting number) must be incorrect.

- Therefore the real numbers represent an infinite set bigger than the counting numbers. \(\quad \blacksquare\)

Such a simple proof. Yet the consequences are monumental.

The size of the real numbers is bigger than that of the counting numbers. It is so big that when we try to fit all the real numbers in a list of counting numbers - they overflow.

We see that not all infinite sets are the same, they have some structure in them. And now, we have the machinery to descibe that. Instead of saying that the set of size is \(\infty\), we can do better - we can find out whether it’s size is \(\aleph_0\) or \(\aleph_1\). ( This is useful because sets in the same size class have some similar properties.5 )

Let us summarize, the sizes we have seen so far:

| Size | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| N = (1,2,3,…) | Sets with a finite number of elements | \(A_1 = \{ 42 \} \ \textrm{(A set with only 1 element - the number 42)}\) \(A_2 = \{ \heartsuit, \diamondsuit, \clubsuit, \spadesuit\} \ \textrm{(Suites in a deck - 4 elements)}\) \(A_3 = \{ a,b,c, ..., z\} \ \textrm{(The english alphabet - 26 elements)}\) |

| \(\aleph_0\) | Sets of the first infinite kind | \(A_1 = \mathbb{N} = \{ 1,2,3,...\} \ \textrm{(Natural numbers)}\) \(A_2 = \{ 1,3,5,7,9,11,13,...\} \ \textrm{(Odd numbers)}\) \(A_3 = \{ 2,3,5,7,11,13,17,...\} \ \textrm{(Prime numbers)}\) \(A_4 = \mathbb{Z} = \{ ..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1,2,3,...\} \ \textrm{(Integers)}\) \(A_5 = \mathbb{Q} = \{ ..., -4/3, -1, 0, 1/2,...\} \ \textrm{(Rational numbers)}\) |

| \(\aleph_1\) | Sets of the second infinite kind | \(A_1 = \mathbb{R} \supseteq \{\frac{-1}{2},\ 0,\ 0.5,\ 1.414,\ \sqrt 2,\ \pi,\ \frac{42}{9},\ ... \}\) \(\textrm{(The real numbers)}\) |

Beyond the proof

The sizes don’t end at \(\aleph_1\). Cantor’s diagonalization argument can be generalized further. We can show that not only there are infinite sets, but that \(\aleph_0\) is the first in an infinite6 hierarchy of infinite sets, each bigger than the last.

The proof is similar to another proof that the counting numbers are infinite. (Have a look below, if you are interested).

<- (click to expand proof)

Here is an informal proof. (It will be easier if you read the left side first)| Suppose N was the biggest counting number | Suppose A was an infinite set with the largest size |

| We can construct a counting number bigger than N ( N+1) | We can construct a set bigger in size than A ( It’s power set: \(\mathbb{P}\)(A) ) |

| So N is not the biggest counting number | So A is not the largest infinite set |

| So our initial assumption was wrong, there is no largest counting number | So our initial assumption was wrong, there is no infinite set with the largest size |

In fact, this generates a new generalization of the Natural numbers - the cardinal numbers:

\(0,1,2,3,\ldots ,n,\ldots ;\aleph_{0},\aleph_{1},\aleph_{2},\ldots ,\aleph_{\alpha },\ldots\)

They are a valid number system, and you can even do arithmetic with them!

Filling the gaps - The Continuum hypothesis

After having discovered a hierarchy among infinite sets, Cantor sought to fill the gaps between his infinite hierarchy.

Cantor’s hypothesis: there is a set with a size between that of the natural numbers and the real numbers.

Cantor tried for many years in vain to prove it.

It took another 63 years and the efforts of 2 brilliant mathematicians to show an astounding result - the hypothesis could neither be proved nor be disproved (in standard set theory)! The continuum hypothesis was among the first mathematical statements that were shown to be undecidable!

(source)

If you have any questions, feel free to ask them in the comments below.

References and footnotes

The size is technically referred to as the cardinality of the set. ↩

The formal version: A set is infinite if it can be put into a 1-1 correspondence with a proper subset. ↩

Exactly representing the reals as a set (with the notation introduced) is complicated. If you want to know more, have a look at the following: wikipedia, MIT math ↩

Now an astute reader may point out: Why don’t we add this “missing” number to our list. Our list would then be complete. But we can make a slight change to fix it, We add this new number in our list and repeat our arguements! And when we find another in our list, we do it again. ↩

As an example, all countably infinite sets are compact (but all infinite sets are not ) ↩

This result is known as Cantor’s theorem ↩